Beatle Loathers Return: Britain's Teddy Boys

Rock and roll fashion revivalists

By Jerry Hopkins , March 2, 1972

London — "You weren't here when the Teddy Boys arrived on the scene in the Fifties," my English friend says. "London doesn't remember them with any fondness. You know those little caps Gene Vincent wore—Gene Vincent and His Blue Caps? The Teds used to put a razor blade in the bill and use the cap as a weapon in fights. Those crepe-soled shoes they wear, they had razor blades sunk in the toes. No, London doesn't remember the Teds with any fondness."

We were on our way to the Black Raven, a small working-class pub in London's sooty east end, where a picture session was planned.

"Awopbopa-loobop, awopbamboom ..." The sound of falling through a time warp.

Outside, parked at the curb, are half a dozen Fifties American cars. Inside there are at least 150 Teds, attired in their weekend flashback best: velvet-trimmed Edwardian suits, jackets reaching mid-thigh, drainpipe pants so tight the Teds look as if they've been dipped in ink, frilly shirt fronts, bootlace ties, glow-in-the-dark salmon and chartreuse sox, suede shoes with thick crepe soles, creepers is what they're called. But no caps. All you can see is hair.

Plumes and cascades and whirlpools of hair, all of it greased and obsidian-black, thumbing its nose at gravity as it stretches four inches from the brow, wobbling, glistening: the classic Elephant's Trunk; sweeping back in shiny sheets past earringed ears to plunge into a perfect D.A. or splash over the velvet collars in hirsute waterfalls. Towers and arches and walls of hair. This isn't just extraordinary styling—it's architecture.

Over there. There's a Gene Vincent. And there's a Roy Orbison. Everyone has a favorite. Maybe it's Carl Perkins, who's right now, courtesy of Sun Records and the Black Raven Golden Oldies Juke Box, "Boppin' the Blues." There's a little leather here, too: motorcycle jackets sprinkled with studs. Tattoos. And from nearly every left ear in the pub there dangles a tiny cross. One Ted has five crosses dangling. Another has had his ear pierced with 20 gold rings. Over the bar, a painting of Elvis, executed by one of the customers. Is all this the Presley legacy?

The pub is crowded, shoulder-to-shoulder, but over near the door, Gene Vincent is dancing—jitterbugging, indeed—with a miniature Wanda Jackson lookalike: back-combed hair that's sprayed just so. The record ends, the Teddy Boy's comb comes out, damage to the architecture is repaired, another oldie plops into place and it's time for another shake: "I'm ready, ready ready ready to-uh, rock & roll ..."

It's staggering when you think about it. Some say there are as many as 20,000 Teddy Boys, in England today, with hundreds more stuffing themselves into the "drapes-and-crepes" each week. The figure may be inflated, but even if it's a quarter that, it's worth noticing, because Teddy Boys were declared extinct back around 1958, and now they have boutiques and pubs and clubs joining their parade at the rate of one or two every fortnight. It's not the rave of trendy London yet—and probably won't ever be—but it's not bad for the once-feared, long-forgotten Ted: England's pop cultch dinosaur.

Bob Acland, the Black Raven's proprietor and father figure, an Original Ted still wearing the drape, sits on a stool at the end of the bar. "These boys," he says, "most of 'em are young boys, they missed this music when it was at its peak. They don't want the music that's being written today because it's all political stuff. The kids today 'aven't 'ad the opportunity to 'ear good clean music, the rock & roll, because all this modern music is political stuff, dirty music. Now they've got a chance to listen to good clean music, with no malice, no politics, no propaganda."

Bob points toward the jukebox. "The only Beatles record I got on there is 'Me Bonnie Lies Over the Ocean,' because at that time, in Munich, Germany, in 1962, the Beatles was good. Then they deteriorated to rubbish.

"I'm not politically minded meself and that's why I don't listen to the Top 20 tunes, because as soon as you listen to one it starts up about a man's skin or a man shootin' somebody else, or you got to take drugs and I don't want to listen to this rubbish."

Of course, there's more to it than that, especially when it's realized that—according to Bob Acland, as good a source as any—fully 80 percent of today's Teds are still in their teens, which isn't childhood exactly, but when rock & roll came by the first time, they weren't even school-age yet.

"You 'ave to admit it's smart," says Bob Acland. "My boys that drink in this pub are the smartest dressed boys in the whole of the country, I might even say the whole of the world."

It's fashion for effect, not function. Soft as velvet, sharp as razor blades. It's possible to be a dandy, yet tough.

* * *

We're back in the early Fifties now. The Teddy Boys, then as today, are working-class—juvenile veterans of the London blitz, seeking an identity and kicks. At the time, the Edwardian style was offered in only the smartest shops, an appeal to modish dignity in a time of rubble and rationing. The precise moment at which the working-class boys adopted the style—and the shocked aristocrats instantly discarded it—has not been recorded. But that's what the skinny little beggars did: took from the rich like grotty Robin Hoods.

The image was a perplexing one: underfed teeners from pinched, oppressive neighborhoods, the bored sons of working war widows and laborers, kids with Cockney accents that will stick them in the working-class for life, striding into the amusement arcades near the Elephant and Castle and the Bricklayers Arms in east London, traveling in herds—in prides!—flick knives in their pockets, razors sunk in their caps and crepes, dressed in the raiment of Victorian gentlemen.

It wasn't just the Edwardian look, says Max Needham, another Original Ted, who writes an Oldies column for one of the English pop papers under the name Waxie Maxie. Part of it was American. Remember George Raft and Paul Muni in all those gangster flicks, Raft tossing a coin in his left hand as a signal that someone was being fitted for a concrete overcoat? The long jacket with the outrageously padded shoulders, the peggers, the long keychains? In America they were called zoot-suiters. In London: spivs. Rhymes with shivs. That was an influence, says Max. So was rock & roll, and in London in the early Fifties Bill Haley was king. In '51 it was "Rock the Joint." "Crazy, Man, Crazy" in '52. Then came "Shake, Rattle and Roll" (in '54) and finally and orgasmically (in '55) "Rock Around the Clock." The titles alone said it all, and with the subsequent arrival of Presley, Vincent and all the rest, the style was set.

"The Teddy Boy was essentially a British fashion trend," says Waxie Maxie. "Rock & roll was an American music. One identified with the other."

But by the end of the decade it was all over. Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens and the Big Bopper had gone down in flames in 1959 and in 1960 Eddie Cochran wrapped his car around a roadside marker while on a tour of England. Elvis was in the Army, turning into the boy-next-door, along with two of England's pop-toppers, Cliff Richard and Adam Faith. In America, Dick Clark was in rigid control and England was soon to be Mr. Acker Bilk's. Rock & roll was dead. The Teddy Boy was a dinosaur.

* * *

"We bloody loathed the Beatles. They absolutely murdered all the originals—Carl Perkins' 'Matchbox,' 'Long Tall Sally,' the rest. We remembered how much better the originals were."

William Jeffrey Jr. talking. Better known as Wild Little Willie, a name picked up when he was president of the Ronnie Hawkins fan club. (It was the title of a Hawkins song.) He says the Beatles literally drove the real fans into the past, that a mimeographed magazine called The Bopping News started England's rock & roll revival. This was one of those esoteric journals for serious collectors.

"It started with just a few of us," he says, "and soon enough there were fan clubs all over England. Buddy Holly. Gene Vincent. Fats Domino. Little Richard. And we started to pull out the old wardrobe, the drapes. For special occasions, of course, when one of the original rockers toured England."

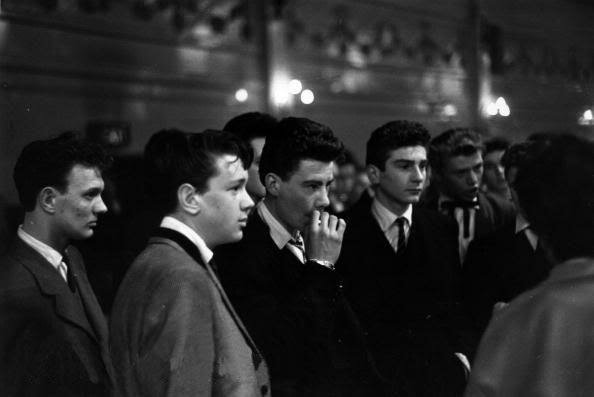

He tells a story about the time Jack Good produced a Jerry Lee Lewis special for British television and he went asking for tickets. Jack was looking for Teds for the audience so Willie was given all he wanted.

"I got in touch with all me pals, and they got in touch with their pals," he says. "We had people coming down from Newcastle, from Scotland, from Wales. There was this great big long queue outside the theater—hundreds of Teds, all in their wildest gear. You've never seen such a band of villains."

It was clear there was something happening.

In 1967 Bob Acland (then, ironically, a chauffeur to the House of Lords) had what he calls "a very good win on a jackpot on the 'orses and I decided to invest me money in some sort of business. My choice was a public 'ouse. This one was on the market. I thought there was a lot of competition around 'ere, 'ow could I build this graveyard up to something? I tried one or two little things, wasn't very successful, and just out of the blue one day I had some old rock & roll records, and for nostalgia and sentimental reasons I thought I'd put them on the jukebox, give meself some of the pleasure of the good old days. I wanted to remember the 'appy times when I was younger, when rock & roll was in its 'ectic stage.

"I found out that the customers in preference to playing the Top 20, they kept playing these old tunes. Then one day, this chap came in and 'e sat down, 'e 'eard this old record and all of a sudden 'e burst into tears. It caused a mem'ry, perhaps an old girlfriend. I went round and asked 'im what was the matter and 'e said the old record sort of dug into 'im. I thought: all right! if it does that, let's put some more on. I kept taking the Top 20 off and soon enough the jukebox was full of the old records: Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis, Billy Riley, the stars that are gone and dead and past, Buddy 'Olly, even Jim Reeves goes down good in 'ere, Big Bopper, Ritchie Valens, the ones that died by tragic circumstances, in car accidents, in aeroplanes.

"I thought: why not dedicate the pub to rock & roll! After a little while the following got so big we started to dedicate three minutes' silence for each star that died under these tragic circumstances, and for each of these stars that are dead we always give 'em three minutes on the anniversary of their deaths."

Bob began scheduling special events, Teddy Boy Picnics he called them, taking the name from the song "Teddy Bear's Picnic," with guest disc jockeys appearing in an upstairs lounge and what he advertised in circulars as "a first class range of hot & cold meals served by our attractive barmaids." When one of those barmaids died in a car accident recently, there was even a highly publicized Teddy Boy Funeral, with headlines in all the London papers: "The Teddies' Lament for Cheerful Cheryl."

The cult spread beyond The Black Raven and occasional television tapings as jukeboxes were restocked in other pubs, at The Castle in Tooting, Small's in the Fulham district, The Swan in Kingston-on-Thames. At the same time, in the cave-like back room of The Fishmongers Arms in the Wood Green section, Saturday night dances offered Screaming Lord Sutch and his out-of-the-coffin bit, two of England's early rockers, Billy Fury and Marty Wilde, and once, shortly before his death, Gene Vincent. Other weekends, up to 600 Teds a night arrived to bop and jive to local, lesser-known bands, the current favorites being Crazy Cavin and His Rhythm Rockers, Shakin' Stevens and the Sunsets, and the Wild Angels.

Today the Teds have their own boutique, Let It Rock, situated on fashionable Kings Road. The walls are papered with movie posters the owners bought from the Elvis Presley Fan Club of Paris when it folded and framed studio stills of James Dean. On the floor are boxes of 45s and stacks of old fan magazines. Two-tone Slim-Jim neckties, flashy combs, 3D rings, jars of hair cream and sequined belts fill a sizable display case.

Until Let It Rock, a Ted couldn't buy his drapes "off the peg"; he had to visit one of the local chains, Burton's, say, or Collier's, and have a suit custom-made, waiting for as long as eight weeks. Now there's a full rack of suits, made by Lord Sutch's tailor, and a wide selection of below-the-knee flare skirts, taffeta imprinted with saxophones and musical notes.

Malcolm McLaren and Mike Martin, the owners, say they were friends in art school—Goldsmith's, Mary Quant's alma mater—when they got a grant to make a movie about Billy Fury. Trouble was, they ran out of money, so they took this high-rent place in Enemy Territory—tourist-trap antique-boutique row—to raise money to finish the flick and, as Malcolm puts it, "to revive the rock & roll."

Malcolm stands there in a wide-lapeled powder-blue sports jacket and luminescent peggers, listening to someone who has an old radio for sale. Let It Rock regularly stocks the old "valve radio," has an old boy about 75—"a radio enthusiast!"—who cleans them up and stands by a three-month guarantee. Malcolm says he's not so sure the radio in question is repairable.

Warren Smith, the boy Sam Phillips hoped would take Elvis' place at Sun in 1955, is wailing on the jukebox.

Malcolm finally takes the radio and goes into a story about the day a full charter busload of Teds arrived.

"They came boldering in 'ere, all dressed up in their gear, their drapes and everything, they spent three hours playing the records, buying glow-in-the-dark sox and pants and magazines. It was quite dynamic, really. All the way from Wakefield in Yorkshire, which is a bloody long way, it really is. It's about 150-200 miles nearly. They'd especially 'ired the coach for the day."

* * *

A group of Teds have been coaxed upstairs at The Black Raven for photographs. They stand around awkwardly, smoking cigars and cigarettes, eying the outsiders suspiciously, striking tough-guy poses that look only slightly out of character. Only when asked about their record collections or clothing do they begin to relax.

"Oy wen' in there an' asked for 13-inch bottoms on me pants an' they looked at me loyke Oy'm crazy, y'know."

"Yuh got thirteens, I got twelves, y'know."

"Yuh must a got feet loyke a gurl."

"Cost me 40 quid [about 100 dollars] and Oy 'ad to buy me own velvet."

"Th' creepers are jus' under six quid, an' look a' this." He grabs his bootlace tie. "Fifteen bob [about two dollars] an' the fuckin' thing's only plastic. Fuckin' scandalous."

How did they get into the Teddy Boy thing?

"To me you cahn't beat rock & roll music," says John Williams, a 30-year-old postman who travels six miles each way to drink at The Black Raven at least three times a week. "It's the joyving, the dahncing, the be-bop, the drype coat, the droynpoype trousers. To me it's the thing."

"It's all Oy ever knew," says another. "Growin' up me brother 'its on me 'ead, 'its on me 'ead, 'Be a Ted, be a Ted.' What else was there? Oy couldn't be anythin' else. Now all me friends are Teds."

"Tha's royght, it's a social community, loyke."

What about all the violence; is that just talk?

"Who yuh been talkin' to?" Bristling slightly. "There's none o' tha' stuff. Oy mean, we don' go lookin' for trouble, but if anybody comes aroun' we don' back off."

"That's the way it is," says another. "Whatever happens, the Teds stick together, yuh always got yuh mates."

It's been quiet lately on the Teddy Boy front. One of the top disc jockeys for the BBC, Tony Blackburn, was sent a razor-blade sandwich some time back, with a message: "If you don't play this rocking record, I'll work this sandwich down you." Someone else sent a bloodstained sock from Cardiff, promising to deliver another with a boot wrapped round it if he didn't play the record. But the anonymous threats were the end of it. Some of the London tabloids are hinting at trouble, with headlines like "Watch Out! The Teddy Boys are Back!" but the stories are appearing on the fashion page.

That doesn't mean that living in the past, even when it's your own past, is without its moments. Take Bob Acland. He's got three kids, 19, 18 and six. The oldest is a Ted, he says, beaming. But the middle boy is a skinhead: "He don't go for the rock & roll, he goes for all this modern rubbish."

Waxie Maxie has it even rougher. He has a daughter, 14, and he says she sneers at his wardrobe and worse than that, when she's off in her bedroom listening to her music—the softer reggae sound—and he's listening to his, sometimes she comes out and tells him to turn the volume down.

It's staggering when you think about it.

From The Archives Issue 103: March 2, 1972